1. Nissim

– The Gaslamp Killer (with Amir Yaghmai)

2. The

Zoo – FEWS

3. Deceptacon

– Le Tigre

4. Low –

Traams

5. Sunday’s

Coming – Eddy Current Suppression Ring

6. Lake

Superior – The Arcs

7. Hollywood

Forever Cemetery Sings – Father John Misty

8. Sketch

for Summer – The Durutti Column

9. Hard

Hold – Jaala

10. Tarantula

Deadly Cargo – Sleaford Mods

11. Excitissimo

– William Sheller

12. Soul Vibrations – Dorothy Ashby

13. Balek – Placebo

14. More Mess on My Thing – Poets of Rhythm

15. All My Tears – The Frightnrs

16. Nightbird

– The Brian Jonestown Massacre

17. The

Wheel – PJ Harvey

18. All I

Wanna Do – Splashh

19. Tied

Up in Nottz – Sleaford Mods

20. Gosh –

Jamie XX

21. Get

Innocuous – LCD Soundsystem

22. Star

Roving – Slowdive

23. Come

Over – Chain & the Gang

24. In the

Mausoleum – Beirut

The Gaslamp

Killer is the stage name of a hip hop producer and DJ from California. 'Nissim' is a reworking of an instrumental

track called 'Yekte' by Turkish

guitarist Zafer Dilek, which itself seems to have been influenced by a track

entitled 'Gurbet' by singer/songwriter Özdemir

Erdoğan. To capture the flavour of the source material The Gaslamp Killer

worked with a guitarist named Amir Yaghmai, who in turn brought in a number of

Middle-Eastern musicians he knew to really nail it. The tune takes a while to

get going, suggesting that it might have worked better further down the

playlist, but Spotify introduced me to it very early in 2016.

FEWS are a Swedish band that play post-punk, although 'The Zoo' also echoes the sound of

shoegaze. It was issued as a single first, in 2015, and then surfaced on the

album Means a year later. 'The Zoo' is reminiscent of British band

TOY but with a greater sense of urgency. Unfortunately for both acts I get

the feeling that the post-punk/garage rock revival has run its

course. Or perhaps we’ve reached a state of perpetual revival where nothing

ever really goes out of fashion but is recycled again and again by way of the

internet.

To add to that thought, you wouldn’t believe that Le Tigre recorded 'Deceptacon' as long ago as 1999. There

are a few clues – the use of an Alesis HR-16b drum machine, a spot of sampling –

but it wouldn’t feel out of step played next to anything around today. The same

could be said of 'Low' by UK band

Traams, released in 2013, and 'Sunday’s

Coming' by Australian group the Eddy Current Suppression Ring, released in

2008. What does this all say about the evolution of music? Is Devo’s theory of

devolution being played out before our ears?

There are subtle differences. As I said, I detect the hint of shoegaze in

FEWS; Le Tigre are quite lo-fi; Traams are sort of punk revival mixed with indie

rock, as are the Eddy Current Suppression Ring. All emanated from Discover

Weekly on Spotify, bar the Eddy Current Suppression Ring which the Australian at work accurately identified as something I might appreciate. What these songs all

have in common is that they’re noisy, loud and faintly aggressive. Such

sonic qualities can be sustained for only so long.

The Arcs are the side-project of Dan Auerbach of blues-rock band The

Black Keys. I don’t mind the Black Keys but I prefer the lo-fi dreampop of The

Arcs. Or rather, I prefer the lo-fi dreampop of 2016’s 'Lake Superior', because the record put out the previous year by The

Arcs does sound a lot like The Black Keys. Perhaps this is the type of

thing that’s now in fashion. Whatever, Father John Misty (real name: Josh

Tillman) inhabits the folkier end of the spectrum, which isn’t surprising given

his involvement with Fleet Foxes. Yet 'Hollywood

Forever Cemetery Sings' is no folksy ditty: it stomps along, demanding your attention.

Only the vocals recall Tillman’s work with his previous band, for whom he

played drums.

The Durutti Column derived their name from the Durruti Column, a phalanx of anarchists

who fought against Franco’s Falangists in the Spanish Civil War. The name

‘Durruti’ acknowledged one of the column’s most admired commanders, Buenaventura

Durruti, who led a pre-emptive attack on General Goded’s barracks in Atarazanas/Drassanes,

ensuring that Barcelona remained under Republican control. Tony Wilson and Alan

Erasmus intended the group as a sort of art statement and set about gathering

musicians to implement their vision. By the time Wilson and Erasmus had

established Factory Records and arranged for The Durutti Column to cut an album,

only guitarist Vincent Reilly remained. Vini Reilly is one of those talented types

who struggle within the music industry (see Syd Barrett, Dan Treacy of the

Television Personalities, Lawrence from Felt). I’d given his music a go before but didn’t get very far with it.

Discover Weekly offered up 'Sketch for

Summer', which is an oddly beautiful instrumental backed by the sound of

tweeting birds.

Jaala: another Australian band, again from Melbourne, but this time The

Australian had nothing to do with it. Singer Cosima Jaala’s delivery is

reminiscent of Lene Lovich – she of 'Lucky

Number' fame, which I included on 2007-08’s Harmony in my Head. 'Hard Hold'

jumps about in a way that can be divisive. Personally, I like their playful

time signatures, but my partner can’t stand them.

I used to share a similar antipathy towards to the Sleaford Mods. A chap

who I worked with during my days as a transcript writer inadvertently brought ‘the

Mods’ to my attention after he posted a video on his blog of them performing 'Fizzy' outside of Rough Trade West. It’s

not entirely comfortable viewing. To start off with, one of the crowd – perhaps

mistaking the occasion for an open-mic event – attempts to get in on the act, and

for a moment it looks like it’s going to turn nasty. Then there’s the way the

group presents itself. Andy Fearn, bedecked in a baseball cap, nods along

nonchalantly. Meanwhile, Jason Williamson’s twitches angrily, constantly rubbing

the back of his head and flicking the end of his nose like he might be on

amphetamine. I think I watched it three times on the bounce. At first I tried to suppress the memory but soon found myself watching

videos for 'Tied Up in Nottz', 'Tarantula Deadly Cargo', 'Jolly F*cker'. I met up with one of the

guys who hadn’t turned up for last year’s Dickensian Pub Crawl, and when I

asked if he’d heard of Sleaford Mods I saw the same glint in his eye that there

must have been in mine. Before long, I was sharing my experience with my

bouldering buddies. Even my boss was intrigued (although The

Australian and the South African sales manager weren’t – I’m not sure it’s the

sort of music that travels well). Come November, I’d bought tickets to see them

play live at The Roundhouse in Camden.

I try to avoid doubling up on artists but I’ve made an exception for the Sleaford

Mods. 'Tarantula Deadly Cargo' is taken

from the album Key Markets, which was

released in 2015. Like most of their music, it’s fairly minimal: a deep,

plodding bass-line layered over a brisk, repetitive beat. Their other

contribution comes later.

An opportunity

had been missed to visit Florence while we were out in Tuscany for a wedding

in 2005. Instead, we’d been persuaded that Siena better catered for day-trips:

it was smaller, slightly nearer, and parking more convenient. Florence is certainly the

more prodigious town, and an afternoon would have never done it justice. Not

that it did Siena justice either, but I was glad now to be going to Florence instead of Siena.

Walking through Piazza Pitti, we turned down a narrow street – Sdrucciolo de’ Pitti – and came across

the sort of shop that my partner likes to browse in, selling a variety of disparate things. What wasn't for sale was the turntable, playing a compilation entitled Wizzz! French Psychorama 1966-1970, Volume

1. I made a note of the details in the back of my guide book and tried to find a copy. Couldn’t locate one anywhere, so ended up ordering

it directly from the record label, Born Bad Records, in France. The track that

had been playing in that small shop in Italy had been an instrumental, which

means it could only have been 'Exitissimo'

by William Sheller.

Wizzz! French Psychorama 1966-1970,

Volume 1 isn’t available on Spotify, so at work I settled for playing the Blue Break Beats series, which had

previously given rise to the inclusion of 'Ain’t

it Funky Now' by Grant Green on my 2000 compilation The Ladies of Varades. The algorithm kicked in and before

long Discover Weekly was offering up tunes as delectable as 'Soul Vibrations' by Dorothy Ashby, a jazz

harpist who recorded for the Chess Records subsidiary Cadet. Ashby struggled to find acceptance within the jazz community; the harp was a classical instrument, and a novelty one at that. Fortunately, in-house

arranger Richard Evans, who had been given carte blanche to work with pretty

much whomever he desired, saw potential and signed Ashby up. Afro-Harping was the result, released in

1968, garnering positive reviews, and where you’ll find the tune 'Soul Vibrations'. (Ashby went on to add

the koto to her repertoire, specifically on 1970’s The Rubaiyat of Dorothy Ashby.)

'Balek' is not an obscure B-side

by alternative-rock act Placebo but an obscure album track by a Belgian jazz

combo of the same name. A guy called Marc Moulin was the prime mover, and his

version of Placebo recorded three albums: Ball

of Eyes in 1971, 1973 in 1973,

and Placebo in 1974. 'Balek' is the fourth track on 1973 and it also makes a showing on It’s a Rocky Road: Volume 2, a mix compiled

by The Gaslamp Killer, which might explain how it ended up here. We’re

talking jazz-funk, but what attracted me to it was the way the second blast of the trumpet is truncated and set slightly ahead of the beat.

The Australian used to put on The Poets of Rhythm, often when he couldn’t

be bothered to look for anything else. They play funk, but as the guy who used

to own a pager was quick to point out there’s something not quite right about

it. This is because they’re not black

Americans recording in the 1970s but white Germans performing in the 1990s. This

was not something I was entirely sure of, but the guy who used to own a pager,

who is a musician, could immediately spot. 'More

Mess on My Thing' is typical of their album Practice What You Preach, and if you like this sort of thing then don’t

let my friend’s musical snobbery put you off.

The Frightnrs [sic]

had me completely fooled. When Spotify generated them, I assumed I was hearing original

rocksteady music from the late 1960s, when in fact it had been recorded as

recently as 2015. The effect is deliberate: the band’s Brooklyn-based record

label, Daptone Records, eschew digital recording techniques and work using analogue

equipment (it’s where Amy Winehouse recorded Back to Black). Moreover, The Frightnrs’s debut LP, Nothing More to Say, was recorded

monophonically. Tragically, their singer Dan Klein died from motor neurone disease

while the record was still in post-production. His vocal possesses a delicacy that seems all the more poignant in light of this, but he leaves a

powerful legacy.

After the bearing witness to the depredations on show in the so-called documentary Dig! it had been gratifying to discover in 2015 that Anton Newcombe continued to produce music to such a high standard. This is not to say that I'd purchased The Brian Jonestown Massacre album Revelation, but I had least deemed another of its tracks worthy for inclusion here – the acoustic 'Nightbird'. [Edit: I ended up buying the album some years later and have bought other BJM records along the way.]

I was excited to discover that PJ Harvey had a new album on the way and bought it almost on the day of release. Plenty of good tracks to choose from but I plumped for 'The Wheel' with its epic 1 minute-plus overture, replete with Iberian hand clapping, wailing guitar and saxophone. The lyric concerns Kosovo and the atrocities committed there.

The single 'All I Wanna Do' by Anglo-Antipodean band Splashh appeared on Discover Weekly, despite being approximately four years’ old. It seems the group were a victim of what’s often termed ‘difficult second album syndrome’. By the time their sophomore effort hit the shelves in April 2017 I’d completely forgotten about them, yet 'All I Wanna Do' remains one of my favourite tunes on this compilation, and I consider this to be a very strong compilation.

The Sleaford Mods in a more urgent mood: the ‘Nottz’ they’re tied up in refers to Nottingham, a town that gets a bad press these days but which I thought was rather pleasant when I went there 20-odd years ago. (Take a drink in Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem if you’re ever passing through).

I don’t like The xx. My primary objection is Oliver Sim’s vocals, which sound like they’ve been cut four sheets to the wind. This is particularly evident in the song 'VCR'. So when my Australian co-worker went to put on In Colour by Jamie xx, who’s the principle songwriter for The xx, I wasn’t expecting much. How wrong I was. 'Gosh' is a very odd tune, at once industrial and harmonic, that draws you in slowly. As The Australian rightly pointed out, it’s best played at a very high volume.

The Australian returned to Australia in early 2017. Before leaving he made a final, unwitting contribution to my playlist by utilising some sort of function on Spotify that randomly plays songs by the same artist, in this instance LCD Soundsystem. 'Daft Punk Is Playing at My House' was massive in the UK, but I never liked it enough to include it on 2005’s Aka 'Devil in Disguise'. Had I heard it I would certainly have made room for 'Get Innocuous!' on 2007-08’s Harmony In My Head, which sounds like a cross between Talking Heads and David Bowie doing disco.

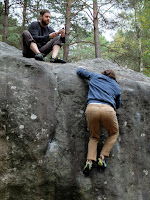

In October, my bouldering buddies and I travelled to Fontainebleau for a third year in succession. I again roomed with Mr Wilkinson, who brought along a musical device and the means by which to amplify it. 'Star Roving' by Slowdive was subsequently amplified, from their new album, their first in 22 years. [The chap who introduced me to Sarah Records and I once found ourselves hanging out with Slowdive at a party in King's Cross – this must have been around 1995. I wasn’t familiar with their music back then and didn’t even realise who they were. It was an awkward situation, made more awkward when Miki Berenyi from Lush came over and offered around canapes. We went outside to consider our options just as Donna from Elastica arrived bearing booze. She smiled at first, and then, upon realising that she didn’t know who the hell we were, regarded us with complete contempt. Elsewhere, Jarvis Cocker played records to an empty room. After an hour or so the guy who invited us still hadn’t turned up, and we decided to leave. With not enough money for a bus, we then proceeded to walk all the way back to Hounslow, which took over four hours.]

My enthusiasm for Chain & the Gang was reinvigorated after 2014’s Minimum Rock n Roll and I made a point of buying their new album on its release. It proved impossible to get hold of on vinyl and I would have to wait until the band toured the UK in February 2018 to obtain a copy. In the meantime, I listened to the record on-line and downloaded the track I wanted for my compilation: 'Come Over'.

After numerous

trips to Spain, Italy and France, I advocated for a return to central or

eastern Europe. And so in the summer of 2016, I flew to

Krakow with my partner for what should have been a relaxing four days and four nights. On the third

night we ate bad goulash, and the rest of the holiday was spent in bed, in the

bathroom, or tentatively wandering around the city’s main square, Rynek Główny.

Before consuming the offending meal, I had been privy to Krakow’s Fair

of Folk Art (Targi Sztuki Ludowej),

centered around Rynek Główny, which consisted of artisanal market stalls and

traditional live music. These musical performances were a delight. They were

more like plays really, acted out by players of various ages wearing

traditional costumes, sang in that distinctive timbre that often typifies the

vernacular.

The following Easter and we were back in Spain, just in time to celebrate

Holy Week in Seville (Semana Santa de

Sevilla). This was not a deliberate move on our part, but it made for an

interesting holiday. We arrived on Holy Monday and departed on Good Friday, and

on every day we were there, at around 16:00 the festivities would commence. Large

floats called pasos, depicting

various scenes pertaining to the crucifixion, were paraded around the city by

their respective cofradías (brotherhoods).

In front, cloaked nazarenos holding

candles; behind, brass bands playing a maudlin sort of mariachi.

There must be so much music from around the world that’s worth listening

to, but who has the time – or even the ear – to sift through it all and decide

which of it is any good? There was a new guy at work who generally played stuff

that didn’t interest me. One day he put on an album called The Flying Club Cup by a group called Beirut. ‘Balkan folk’ is how

Wikipedia describes it, but the band are from the state of New Mexico. 'In the Mausoleum' was the track that

jumped out, and I made a note of it. Although sung in English, it feels

authentic, even though it can’t be. Or can it? Band leader Zach Condon

travelled around Europe in his early teens, and he cites the films of Federico

Fellini, the mariachi music he was exposed to growing up in Sant Fe, and French

chanson as influences. He’s not appropriating anything but absorbing various

influences and reinterpreting them. And now, like Bombay Bicycle Club did, he’s

stopped doing that, and Beirut’s music, like Bombay Bicycle Club’s, has taken a

very average turn.

[Listen to here.]

.JPG)